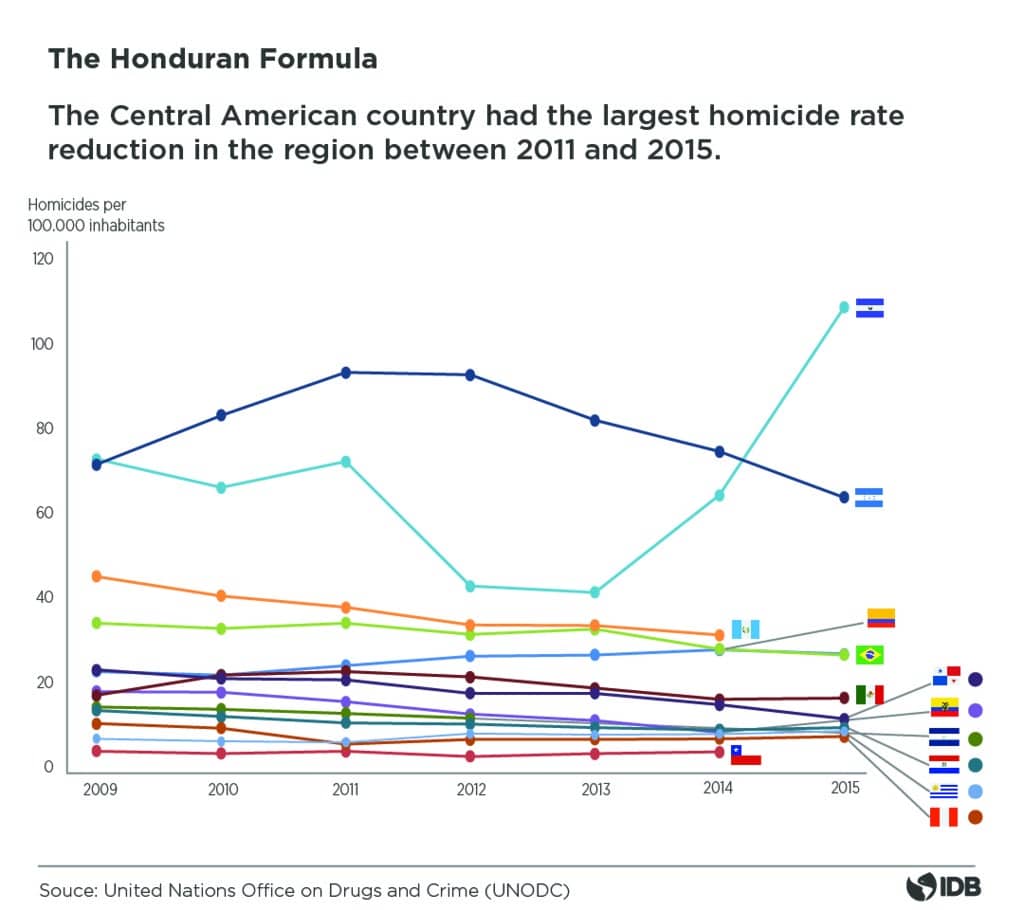

In 2011, Honduras headed a ranking that no country would like to lead: it had the highest homicide rate in the world, with 93.2 people killed per 100,000 inhabitants. The feeling of insecurity was widespread and few people trusted the police when they were victims of a crime. The distrust was so severe that 78.5% of Hondurans did not believe that the police was capable of fighting violence, according to the Latinobarometro survey 2011.

"We were in a crisis because the institution of the police had a crisis of credibility," says General Julian Pacheco Tinoco, Secretary of Security for Honduras. "The problem was so serious that we even analyzed scenarios to close the police," he says.

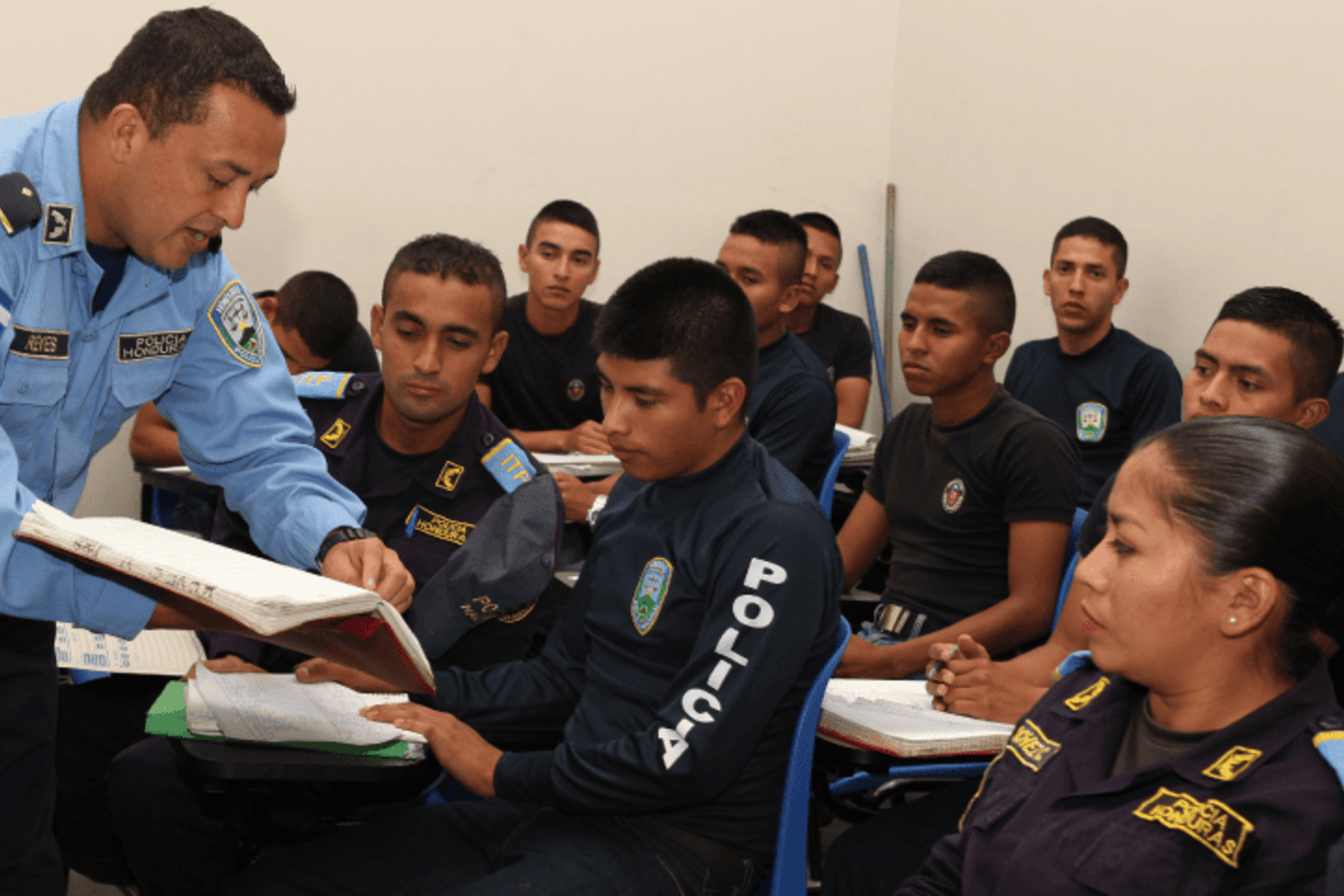

The experts pointed out that a comprehensive reform of the police was needed, starting with the modernization on how to actually instruct and train new police force. Back then, the curriculum was outdated, the teachers did not have adequate training and the recruitment criteria was weak. Specially policemen and women who were at the basic scale, which accounted for 90% of the police force. These officers are those with whom people most interact, but ironically the ones who also had serious deficiencies in their education.

In 2012, the Honduran government began a process to reform its police forces. As part of this objective, the IDB —together with the Swiss cooperation agency— assisted the Honduran government to create a program aimed at strengthening the capacities of the police at their initial stages, while improving the management of criminal investigations.

"If you want to change a person, if you want to change an institution or even a country, you can only do it with education," says General Pacheco Tinoco.

The first step was to strengthen the admission criteria for new police officers. Before the reform, prospective officers only needed a primary school diploma in order to gain admission to the police academy —better known as the Police Technological Institute or ITP, in Spanish. With the reform, requirements were raised up to a high school diploma, as well as new measures were instituted to recruit more women into the police force.

The second step was to improve the quality of education. A new curriculum was created with an emphasis on community-building and respect for human rights, in renovated facilities with better teachers. The duration of the training was extended from 6 to 11 months, with a new methodology that combined a theoretical approach with practices in the field. While also expanding the infrastructure to serve a larger female student population. As of today, more than 4,000 agents have completed this new program.

The goal? To graduate 23,000 agents by 2023.

"The values that we carry all of our lives are molded and strengthened at the ITP," says investigative agent Yulisa Merlo. "Everyday they teach us that we have to nourish respect for other people and oneself, too," she says.

The process: Honduran police force under training

The third step was to increase the technical capacity and equipment of the police, with a focus on improving crime prevention efforts. With this aim, an information system was developed so that it could facilitate the operational control of all police units, while equipping every patrol car with a computer with access to institutional databases. New equipment and crime laboratories were also financed to improve criminal investigations.

All these improvements were accompanied by actions to dignify the living conditions of police officers. Their salaries were increased by more than 40% and social security benefits were enhanced, with an added component of specialized medical services for female officers.

The combination of a more targeted recruitment process for women, and a greater range of facilities and social services designed for them, contributed to an increase in the percentage of females in the police force to 20%, twice as much as it was before the reform.

"Honduras, as a woman, hurts. Not only men are murdered, every day we see more femicides," says agent Yulisa Merlo. "It hurts because I just think that one day it could happen to my sister. But we have to put aside our feelings and focus on doing the job," she says.

The improvements in working conditions also came with higher expectations on work performance. In collaboration with civil society organizations, a commission was formed to dismiss those officers who did not meet a set of standards or perform their duties effectively. So far, more than 4,000 police agents have been removed from service after a careful evaluation.

Video: How can we include more women into our national police forces? (in Spanish)

Overall, the reforms have been highly effective. The homicide rate plummeted from 93.2 to 42.8 per 100,000 inhabitants between 2011 and 2017. According to the Gallup Global Survey, the percentage of citizens who reported feeling safe walking in their neighborhoods increased by 11 percent from 2015 to 2016. In addition, an annual survey conducted by the Government of Honduras revealed that citizen confidence in the police tripled, from 19% in 2015 to 54% in 2017. Although there is still much work to be done, Honduran citizens feel safer and have more trust in their police force. Agents are also happier, with better living conditions, greater technical skills to carry out their job, and proud of what they do for society.

"We have a creed that says that being a police officer is a costly honor," says agent Yulis Merlo. "Everyday we endure risks and wearing a uniform does not makes us invincible, we are not Superman or Superwoman. It's an honor that carries with it a cost, but it's an honor."